On Election Day this month, just two Conroe, Texas, voters were the entire electorate for one of the biggest bond proposals on U.S. ballots, a $468 million sale that will transform the pinelands around a former Boy Scout camp into a sprawling community. Both of them approved.

The small-scale referendum is part of a record-setting trend in the Lone Star State, which has been picking up more than a thousand new residents a day. Texas special districts like the one in the Houston suburb, drawn up around virtually unpopulated tracts owned by developers, are borrowing billions to build roads, sewers and water lines needed for new houses. It’ll be repaid — eventually — by property owners.

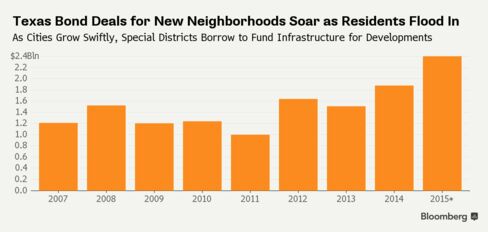

With its population growing more than any other state, Texas is awash in the type of municipal bonds that flourished in Florida and California during the housing bubble, only to burn investors with losses after real estate prices crashed. Its districts are on pace to sell more than $2.5 billion of the securities this year, the most since at least 2007, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At least $1.7 billion more were approved on Nov. 3.

“It’s been a busy 10 years,” said Richard Muller Jr., a lawyer in Sugar Land, Texas, who works with about 20 districts, including the one in Conroe. “We’re still catching up to all the new jobs the state added.”

The securities have been a draw to tax-exempt bond buyers who are looking for higher yields as interest rates in the municipal market hold near a five-decade low. When the Fort Bend County Municipal Utility District No. 194, some 23 miles (37 kilometers) southwest of Houston, sold $5.1 million of bonds on Nov. 5, the 10-year debt yielded 3.2 percent. That’s a percentage point more than top-rated securities.

“If you have the skill set you can pick up some additional yield, as long as you do your homework,” said Colby Harlow, president of the hedge fund Harlow Capital Management in Dallas. “You have to be super selective and look at them on a case by case basis.”

So-called dirt bonds are paid through a special tax levied on the property, which is typically covered by the developer until the homes are sold. The risk: That the homes never sell or tax bills aren’t paid.

While sales of the bonds shriveled in Florida and other states after the housing-market rout left new developments vacant, they’ve continued in Texas, home to five of the 10 fastest-growing cities last year.

After the oil-industry bust of the early 1980s pushed more than a dozen districts into bankruptcy, Texas lawmakers provided safeguards for investors: It required developers to begin paying for the infrastructure up front. They’re reimbursed later when bonds are sold.

“Dirt districts are dirt districts no more,” said Omar Tabani, an analyst with Standard & Poor’s in Dallas. “The developer fronts the cost and doesn’t get reimbursed until the district results in enough taxpayers to pay the debt.”

Surviving Recession

In March 2009, S&P raised the ratings on 250 of the Texas districts because few homeowners were falling behind on their tax bills, even though the recession still hadn’t ended. Since then, property values have continued to rise in the Houston area, where 80 percent of the districts are based, to more than $500 billion from a little over $300 billion in 2007.

“MUDs were the ugly stepsister of the municipal-bond market for many years,” said David Jaderlund of Jaderlund Investments in Santa Fe, New Mexico, who invests in Texas debt for clients. “The debt was issued, but there weren’t any buyers for the property. Now that’s not true any more.”

In Conroe, a city with some 66,000 residents about 40 miles north of downtown Houston, the debt will help build a 2,046-acre planned community called Grand Park Central, which will include residential neighborhoods, retail shops, office space, hotels, restaurants and a conference center. It’s not far from one of Exxon Mobil Corp.’s offices.

Oil’s Impact

One risk looming over the Texas real estate boom is the oil-price bust. A sustained decline in crude would eventually hurt employment and drive down property values, said Tabani, the S&P analyst. In the Houston area, home prices have continued to rise, even though oil is trading for about $40 a barrel, less than half what it was about a year ago. New home construction in the state rose 7.5 percent in August, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

“Today the land developer has skin in the game before they even sell bonds,” said Doug Benton, senior municipal credit manager for Cavanal Hill Investment Management, a Tulsa, Oklahoma-based company that handles about $6 billion, including Texas municipal bonds. “If we feel there is value that can be had, it is definitely a bond we will look at.”

Bloomberg Business

by Darrell Preston

November 15, 2015 — 9:01 PM PST Updated on November 16, 2015 — 6:39 AM PST