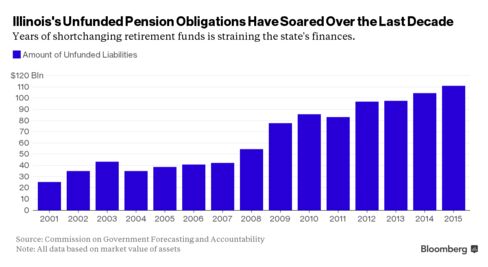

As 2015 draws to a close, Illinois marks half a year without a budget. No spending plan has driven up borrowing costs, sunk its credit rating, and perhaps worst of all, exacerbated the state’s biggest problem: its underfunded pensions.

Home to the least-funded state retirement system in the nation, Illinois has $111 billion of pension debt, which breaks down to more than $8,000 per resident. Partisan gridlock has produced the longest budget impasse in Illinois history. The stalemate has not only weakened state finances, it has kept lawmakers from finding a fix for those mounting liabilities.

“The delay on the budget is definitely delaying anything being done about the pensions,” said Dan Solender, head of municipals at Lord Abbett & Co. in Jersey City, New Jersey, which manages $17 billion of local debt, including Illinois general-obligation bonds. The firm is underweight Illinois. “The longer you wait to try to catch up on funding, the worse the situation gets.“

Illinois’s fiscal health will deteriorate further without a budget, hindering its ability to mend its pension system. Moody’s Investors Service dropped Illinois, already the worst-rated state, to the lowest investment-grade tier in October as the budget stalemate dragged on. Last month, Moody’s warned that pensions are Illinois’s “greatest challenge.”

It’s been seven months since the Illinois Supreme Court rejected the state’s solution. Justices threw out the 2013 restructuring that took six attempts over 16 months to pass, despite one-party rule at the time. The measure was projected to save $145 billion over 30 years by limiting cost-of-living adjustments and raising the retirement age.

Illinois enters 2016 snarled in partisan bickering as Governor Bruce Rauner, the state’s first Republican chief executive in 12 years, and the Democrat-controlled legislature can’t agree on annual appropriations, much less an overhaul of a retirement system that must withstand an inevitable legal challenge. The state constitution bans reducing worker retirement benefits.

In July, Rauner laid out a plan to create a tiered system to cut retirement liabilities. At the time, he said it would save taxpayers billions of dollars. The proposal, which included a measure to allow municipalities to file for bankruptcy protection, was never introduced, according to Catherine Kelly, his spokeswoman.

Standard & Poor’s removed Illinois’s A- rating from negative watch on Wednesday, a designation that usually signals a downgrade is imminent. In doing so, the New York-based company kept Illinois one step higher than Moody’s and Fitch Ratings. Fitch dropped Illinois in October to BBB+, the third lowest investment grade, and Moody’s cut its rank to the equivalent Baa1 later that month.

Rauner and members of his administration have regular talks on pension reform with the four legislative leaders and their staffs, according to Kelly, who reiterated the governor’s call for structural changes like term limits and property tax relief.

“Illinois’ pension crisis is one of the most pressing issues facing the state, and common-sense reforms are needed to achieve real savings in our pension system to ensure its long-term viability,” Kelly said in an e-mailed statement.

Illinois is set to pay about $7.5 billion to pensions this fiscal year, and another $7.8 billion in the year that starts July 1, according to the Civic Federation, citing preliminary estimates by the retirements systems.

Delayed Payment

Even with the record budget impasse, about one of every $5 from the state’s general fund coffers is going toward pensions, according to a Civic Federation report that cites estimates from Illinois Senate Democrats published on Aug. 13. The state’s four plans are only 42 percent funded based on the market value of assets, according to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability. That compares to 60 percent a decade earlier.

The lack of a budget forced the state comptroller to delay a $560 million November payment to the state retirement system. Illinois’s unpaid bills totaled $7.6 billion as of Dec. 18, according to that office. The November retirement payment will be paid in the spring when the state has more revenue from income tax collections, according to the comptroller’s staff.

Investor Confidence

While Comptroller Leslie Geissler Munger has said bond payments are prioritized, the lack of budget has shaken some investors’ confidence. Illinois hasn’t sold bonds since April 2014, a record borrowing drought.

The spread on its existing debt has widened. Investors demand 1.8 percentage points of extra yield to own 30-year Illinois bonds, the most among the 20 states tracked by Bloomberg. When the spread climbs, that’s reflecting that investors think the problem is getting worse, said Richard Ciccarone, Chicago-based chief executive officer of Merritt Research Services.

“What’s the root cause of why we’re in the problem we’re in?” Ciccarone said. “It’s down to the pensions.”

Illinois is like a patient in the emergency room, said Paul Mansour at Conning, which oversees $11 billion of munis, including Illinois securities. The budget stalemate is the crisis at hand, and the unfunded pension liabilities is the chronic disease that’s only getting worse. The budget standoff is hurting future negotiations on pension changes, he said.

“It’s not an atmosphere of conciliation and compromise,” said Mansour. “It’s an atmosphere of conflicts.”

Bloomberg Business

by Elizabeth Campbell

December 22, 2015 — 9:00 PM PST Updated on December 23, 2015 — 11:37 AM PST