When Chicago’s city council this month delayed voting on a bond sale sought by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the elected leaders questioned whether they should go deeper in debt to pay about $100 million to unwind derivative trades.

“My fear is that these products designed to offer savings are going to saddle us with two decades of payments,” said Chicago Alderman John Arena, who joined with others to hold up consideration of the deal. “Is borrowing to pay the termination payment with more debt the way to buy our way out?”

Even in Chicago, a city contending with soaring pension bills and a school system that’s veering toward insolvency, there’s little other option. States, cities and counties across the U.S. haven’t found a way to skirt the fees they still face from interest-rate swap deals that cost them billions since credit markets unraveled in 2008. Chicago alone has paid $250 million to break the contracts, which banks had the right to cancel after its credit rating was cut to junk by Moody’s Investors Service in May. That’s enough money to cover more than two months of payroll for the city’s police department.

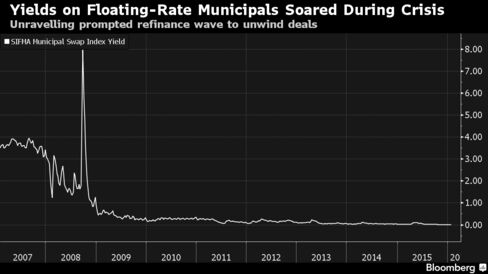

The derivatives were intended to protect governments that sold variable-rate bonds from the risk that interest costs would rise. They agreed to pay a fixed rate to banks in return for those that fluctuated with market indexes. Those adjustable payments were supposed to cover the interest due on the debt, leaving governments effectively paying the fixed rate. It could be cheaper than borrowing by selling traditional securities.

When the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero in late 2008, the trades became valuable assets to banks, and governments had to pay the market value if they wanted to break them. Some unwound them because the deals backfired, resulting in higher debt bills, while others opted out so they could refinance after borrowing costs dropped to a half-century low.

Public officials have no recourse but to honor the contracts, absent unusual legal circumstances: Detroit reduced its obligation only because of its bankruptcy, while JPMorgan Chase & Co. forgave Jefferson County, Alabama’s $647 million of fees to settle Securities and Exchange Commission charges of fraud.

“They see it as a piece of paper that is a contract, they don’t think they have to negotiate,” said Robert Fuller, a principal at Capital Markets Management, a Hopewell, New Jersey-based swaps adviser.

Chicago has had some success. The city estimates that it has saved about $20 million by negotiating with banks over the market value of the derivatives contracts it has already canceled, according to Carole Brown, its chief financial officer.

Molly Poppe, a Chicago spokeswoman, said Royal Bank of Canada and Barclays Plc are counterparties on the derivatives the council considered this month. Elisa Barsotti, a spokewoman for RBC in New York, and Mark Lane, a spokesman for Barclays, declined to comment.

Officials in Harris County, Texas, and Los Angeles explored ways to reduce what they owed to banks, only to later abandon the efforts without success.

Political Push

In Chicago, labor unions facing pension-benefit cuts have pushed for officials to challenge the fees, saying the city wasn’t fully apprised of the risk.

“If you pay now the taxpayers will end up paying for them for the next 30 years,” said Saqib Bhatti, the director of ReFund America, which has been working with unions and other groups on the swaps. It’s backed in part by the Roosevelt Institute, a think tank that looks for ways to restructure government. “It doesn’t put the deal behind you, it puts it on the books so you’re paying it for the next 30 years.”

In 2014, Chicago’s lawyers looked into whether there were grounds for a legal challenge by interviewing current and former employees and pouring through thousands of pages of documents. They didn’t find any basis to sue.

“If we thought there was a valid claim that we could pursue against the swap counterparties — please be assured we would vigorously pursue it,” Jim McDonald, a city attorney, told reporters on a conference call this month. “We had a very thorough review done, and we did not find a legal basis for pursuing any such claim.”

On January 13, Chicago’s city council held off on authorizing a $200 million bond issue that would cover the derivative-cancellation fee. Brown, the CFO, will discuss the deal with city council members at a meeting again next month.

The financing would finish Emanuel’s plan to eliminate the risks tied to such deals, which have triggers that give banks the right to demand that bonds be paid off early and the derivatives canceled if the city’s ratings fall below a certain threshold.

Poppe, the city spokeswoman, referred to Brown’s previous remarks when asked to comment. In a Jan. 21 letter to aldermen, the CFO said the city continues to “aggressively negotiate the water swap termination payments to ensure the smallest payment possible.” Barclays, which took over part of a water-bond swap from UBS AG, lowered the rating threshold, which prevented Chicago from facing an immediate demand to pay it off.

Officials probably never should have entered the agreements in the first place, said Richard Ciccarone, who follows municipal finance as president of Merritt Research Services in Chicago.

“They should have turned them down because they involved betting the public’s money on interest rates,” said Ciccarone.

Bloomberg Business

by Darrell Preston and Elizabeth Campbell

January 28, 2016 — 9:01 PM PST Updated on January 29, 2016 — 5:35 AM PST