When Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin proposed his budget in January, he told lawmakers the teacher retirement system had $13.9 billion less than needed to cover promised pension benefits. The state’s audited financial statements earlier estimated the shortfall was about 55 percent larger, at $21.6 billion.

The discrepancy for the pension that serves 122,000 current and former school workers didn’t result from a secret investment windfall that slashed its debt. It’s because of a gulf that’s emerged between official figures that are disclosed to municipal-bond investors — and those states and cities can rely upon when deciding how much they need to pay into their retirement funds.

New accounting rules that took full hold last year prevent governments from counting on investment returns after they’re broke, a technique that masked the scale of the debts they face as workers retire. But outside of their certified books, they’re free to sideline it.

“There is great confusion about the numbers and what they mean,” said Robert North Jr., former chief actuary for New York City’s pension funds. “Whatever numbers are used are dependent on how they are created, what they represent and their purpose.”

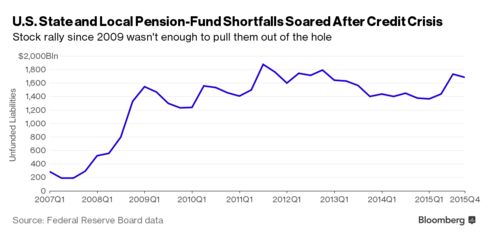

The strains of America’s public pension funds have taken on renewed importance since the credit crisis, which saddled them with investment losses from which they haven’t fully recovered. By the end of 2015, state and local government retirement systems had $1.7 trillion less than they will eventually need, up from a $293 billion shortfall eight years earlier, according to Federal Reserve Board figures.

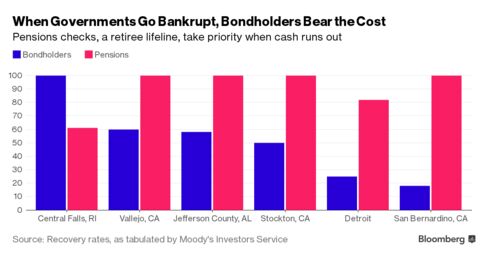

Because governments typically count on investment returns of more than 7 percent a year, when they fall short of that they need to pump additional money into the funds to catch up. Such financial pressure led Moody’s Investors Service to cut Chicago’s bond rating to junk last year and threatens to exaggerate the fiscal crisis in Puerto Rico. It can also pose risks to municipal-debt investors if a government goes broke: In the major bankruptcies that followed the recession, bondholders bore deeper losses than retirees.

The changes from the Governmental Accounting Standards Board were aimed at addressing concerns that states and cities were using investment-earnings forecasts to minimize the size of their unfunded debt to retirees.

As a result, when putting a current value on pension obligations due far in the future, they now have to use less aggressive assumptions for the years after they run out of cash. That increases the stated liability.

The standards, which aren’t required by federal regulations, don’t mandate how governments calculate their annual payments into the funds, said Keith Brainard, who tracks pensions for the National Association of State Retirement Administrators.

“Systems are generating two numbers for two different purposes,” said Brainard. “One for accounting and one for funding.”

The difference can be significant. When New Jersey sold bonds earlier this year, it put both in the official documents that were provided to investors. Under the old accounting standard, it’s unfunded liability was $43.8 billion. Under the revised one, $78.8 billion.

With the new rules, the funding level of the Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System is 45.6 percent, meaning it has 45.6 cents for every dollar it owes, according to the annual financial report released in December.

Governor Bevin used the more well-funded level of 55.3 percent when asking the legislature to determine how much money the state needs to allocate for the pension.

The higher figure is reflection of different assumptions, said Mark Bunning, Kentucky’s deputy finance secretary. “The numbers we use can change over time as assumptions about investment returns evolve,” he said.

If the funding level is higher, governments don’t have to pony up as much, which means they may eventually not have enough to cover what they owe to retirees, said Chris Tobe, a pension consultant who previously served as a trustee of the Kentucky Retirement Systems.

“They have to use GASB when they issue bonds, but when they seek funding from the legislature it’s better to go with higher numbers,” said Tobe. “The larger numbers make them look better funded and then they don’t have to raise taxes or cut spending on education.”

The accounting standards setter anticipated that government officials would take time to get used to the new rules.

“It’s something we would expect during this transition period as some take comfort in having the old numbers,” said Kip Betz, a spokesman for GASB. “I expect we’ll evolve away from that over time.”

In the meantime, it’s sowing some confusion about the financial health of the retirement plans. “The public would have a better understanding if the two numbers could be reconciled in a way that would make clear what they mean,” said David Crane, a lecturer of public policy at Stanford University.

Bloomberg Business

by Darrell Preston and Neil Weinberg

April 27, 2016 — 2:00 AM PDT