Since Chicago was cut to junk by Moody’s Investors Service in May 2015, the city has sold more than $3.3 billion of debt, allowing it to avoid potentially devastating bank penalties triggered by the downgrade, and pushed through a record property-tax increase.

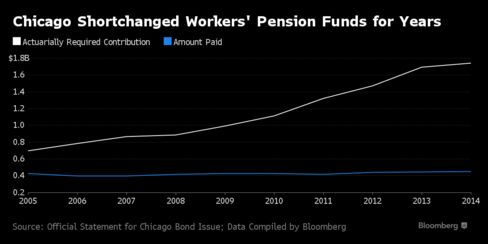

But the triage over the last year has done little to loosen the financial bind that tarnished its standing on Wall Street in the first place: A $20 billion pension-fund deficit that’s adding hundreds of millions of dollars a year to its bills, a legacy of long promising workers more in benefits than officials were willing to fund.

“All of this progress may not mean much if they don’t finish the job,” said Ty Schoback, a senior analyst at Columbia Threadneedle Investments, which holds about $300 million of Chicago debt among its $25 billion of municipal securities. “They need to start finding the money to put into those funds now. Not six months from now. Not 12 months from now. They need to do it now.”

The Windy City, the biggest in the U.S. with a below investment-grade rating, has become a key locus of distress in the $3.7 trillion municipal-bond market, contending with some of the same strains that helped push Detroit into a record bankruptcy three years ago. Reeling from debts that have been building for decades, Chicago’s push over the past year to steady its finances illustrates the difficult way out for cities and states that have saved $1.7 trillion less than they need to cover pensions due in the years ahead.

“We have overcome a large number of hurdles,” Chicago’s budget director Alex Holt said in an interview at City Hall. “It doesn’t mean that there are not some big hurdles that are ahead of us, particularly in the case of pensions.”

Chicago underfunded its retirement system by $7.3 billion in the decade through 2014, city records show, freeing up cash to spend on salaries, roadwork and other routine bills. That’s put it under pressure to set more taxpayer money aside to keep from falling further behind.

The Moody’s downgrade threatened to worsen the city’s financial burdens by exposing it to as much as $2.2 billion in costs to repay floating-rate debt early and call off related derivative trades, which banks had the right to demand. To skirt that, the city pushed through a wave of bond issues as investors demanded yields higher than those on some speculative municipal securities.

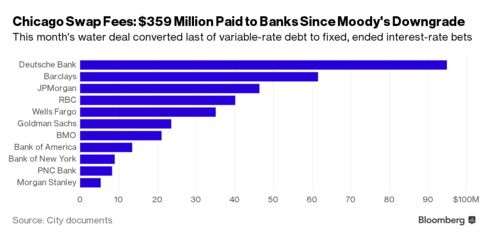

It also paid $359 million to scuttle the interest-rate swap contracts, eliminating the risk of having to settle them when money couldn’t easily be raised.

“They acted quickly,” said John Miller, co-head of fixed income at Nuveen Asset Management, which oversees $110 billion of municipals and bought Chicago debt after the downgrade. “The rates they’re getting on the new issues that they’ve done are pretty manageable.”

Chicago also showed elected officials are willing to raise taxes to chip away at the debts. With support from Democratic Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who was re-elected to another four-year term in April 2015, the city council in October voted to boost real-estate levies by $543 million over four years, the biggest jump ever.

The increase will bolster funding for two of its funds, the police and fire pensions, which were only about a quarter funded as of December 2014. Even so, Emanuel has petitioned Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner to let the city put off about $845 million of pension payments it’s supposed to make over the next five years, which would add to future bills. Rauner has until May 31 to approve that law, which would give the city 40 years — instead of 25 years — to make its retirement plans 90 percent funded.

Even with the property-tax increase, the pension obligation is poised to grow each year and the city has little power to alter benefits. In March, the Illinois Supreme Court dashed Emanuel’s plan to cut cost of living adjustments and require workers and the city to pay more into the municipal and laborers pensions.

“We acknowledge the steps that the city has taken over the last few months,” said Matthew Butler, Moody’s lead analyst on Chicago. “The path to improving the pension situation is likely going to be on the city. It’s going to be increasing contributions to those plans.”

The city is working to come up with a new way to shore up the pensions, including how to raise revenue, according to Chief Financial Officer Carole Brown. The municipal and laborer plans are on track to run out of money in 10 and 13 years, respectively. If they do, more than half of the budget could be devoted to retirement bills, according to Moody’s.

Any overhaul may prove politically difficult. Sixty-two percent of Chicago residents disapprove of Emanuel’s job performance, according to a survey by the New York Times and the Kaiser Family Foundation released this month. The mayor’s standing has been weakened since last year’s release of a video showing a white police officer shooting a black teenager 16 times, which sparked protests decrying the law-enforcement tactics used in Chicago’s minority neighborhoods.

The ongoing financial uncertainty has pushed investors to demand high yields to hold Chicago’s bonds instead of top-rated debt, even though the city’s borrowing costs have dropped amid a rally in the municipal market.

Chicago bonds issued two weeks after the Moody’s downgrade that mature in 2037 priced to yield 5.77 percent, data compiled by Bloomberg show. By contrast, investors demanded just a 4.88 percent rate on a portion of the city’s January bond offering due in 2038.

Those bonds still trade at a higher rate than debt issued for an upstart methanol plant in Texas, a fertilizer facility in Iowa and even some junk-rated tobacco bonds, which Moody’s projects to almost-surely default. Chicago’s city council on Wednesday approved selling an additional $600 million of general-obligation bonds, an issue that’s set to come to market in the third quarter.

The volatility that rattled bondholders after last year’s downgrade is likely to be more muted, said Nuveen’s Miller.

“The move last summer was the big one,” said Miller, who may buy more Chicago debt. “You have to be prepared for bumps in the road on a credit like this, but I don’t think they’ll be 200 basis point moves, and you can earn a decent amount of yield along the way.”

Bloomberg Business

by Elizabeth Campbell and Brian Chappatta

May 18, 2016 — 2:00 AM PDT Updated on May 18, 2016 — 11:22 AM PDT