With U.S. bond yields near record lows, municipal-debt investors are finding a way to pick up a little extra return: Buying lower-coupon securities, which provide fatter payouts because they’ll be harder hit once interest rates start to rise.

The discrepancy was on display when Massachusetts sold bonds late last month. The state paid a 2.18 percent yield on those maturing in 2038 that pay annual interest of 5 percent. For debt with a 3 percent coupon, the yield was half a percentage point more.

Even such a small pickup can be alluring with negative interest rates overseas, Treasuries paying near record lows and the difference between long and short-term municipal debt narrowing to the least since 2008 — meaning there’s less extra income for holding the longest-dated securities. And the risk that the Federal Reserve will soon tighten monetary policy appears to have receded: prices in the futures market suggest a rate increase isn’t likely until the second half of 2017.

“Absolute levels of rates are getting so low that for people, particularly high-grade buyers afraid of credit risk, a strategy to outperform is to buy lower coupons,” said Peter Block, managing director of credit strategy at Ramirez & Co Inc., a New York-based underwriter.

The discrepancy stems in part from a quirk of the $3.7 trillion municipal market, where most state and local governments give themselves the option to buy bonds back before they’re due — usually in a decade — in case they can be refinanced at lower costs.

Because interest rates have largely been on a steady decline since the 1980s, governments have almost always exercised that option. If rates were to rise, which would cause prices of outstanding bonds to fall, those with rock-bottom coupons are more likely not to be called back, leaving investors with the choice between selling at a loss or holding them until maturity.

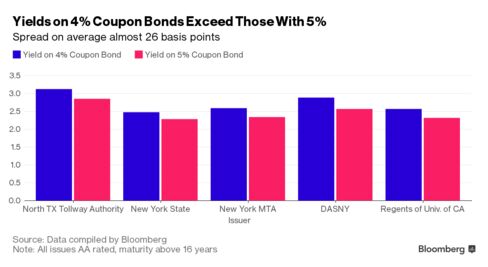

For bonds with top tier credit ratings, that risk has caused investors to demand about one-quarter percentage point more in yield to hold 10-year bonds with a 4 percent coupon instead those set at 5 percent, Block said. Some mutual funds also have little option but to buy the lower-coupon debt, he said: Many are restricted from paying too much above the bond’s face value. As yields have declined, the price of fixed-income securities with higher annual interest payments has soared.

“The question is,” he said, “Will four’s become the new five’s? Will orange become the new black?”

Bloomberg Business

by Molly Smith

July 13, 2016 — 2:00 AM PDT