On a muggy afternoon in April, Angelina Iles, 65, folded herself into my passenger seat and took me on a tour of her beloved Pineville, La., a sleepy town smack in the middle of the low, wet state. We drove past spaced-out, low-slung houses and boarded-up businesses — shuttered restaurants, a decrepit gas station — as Iles, an African-American retired lunchroom worker and community activist, guided me toward the muddy banks of the Red River. Near there stands the locked-up Art Deco shell of the Huey P. Long hospital, which once served the poorest of the poor in Rapides Parish — and employed more than 300 workers.

When employers leave towns like Pineville, they often do it with a deaf ear to the pleading of state and local governments. But in the case of Huey P. Long, the employer was the government itself. Its demise began, arguably, in 2008, when Bobby Jindal was swept into the Louisiana governor’s mansion on a small-government-and-ethics platform, promising to modernize the state and unleash the power of American private industry along the Gulf Coast. At the time, Louisiana was flush with federal funds for Hurricane Katrina reconstruction and running a budget surplus. Jindal and the State Legislature slashed income taxes and started privatizing and cutting. This was a source of great pride for Jindal. During his failed bid for the presidency last year, he boasted that bureaucrats are now an endangered species in Louisiana. “I’ve laid off more of them than Trump has fired people,” he said, “and I’ve cut my state’s budget by more than he’s worth.”

He laid off more than just bureaucrats. Jindal cut appropriations for higher education, shifting the cost burden onto students themselves. (State spending per student was down more than 40 percent between 2008 and 2014; just one state, Arizona, cut more.) And he shuttered or privatized nine charity hospitals that served the state’s uninsured and indigent. They were outdated and costly, Jindal argued, and private management would improve access, care and the bottom line. Huey P. Long was one of those hospitals.

Iles, along with dozens of other workers and activists, helped organize a protest against the cuts, she told me. They held a vigil on the hospital’s front lawn. Iles even helped produce an anti-Jindal documentary called “Bad Medicine” that was broadcast on local television. But it was all for naught. “The good governor did not want to listen to us,” Iles said, checking her constantly buzzing phone in the car. The hospital closed its doors in 2014, and its patients were redirected to other local medical centers and clinics. All of the hospital’s workers lost their jobs.

Driving around Pineville, Iles and I dropped in on a friend of hers from church, Theresa Jardoin, 68, who worked in the hospital for 41 years, most recently as an EKG supervisor. Out of work, she spends most of her days at home, taking care of her family. Earlier, Iles had introduced me to another friend, Linette Richard, whose story was similar. She had been working as an ultrasound technician when the hospital closed. She lost much of what she had been expecting for her retirement, because she had not been there long enough. “Nobody’s jumping to hire a 58-year-old, especially in my field,” Richard said. “You can get a low-paying job, like McDonald’s or Burger King. But higher up? We don’t have positions available. That’s the way it is.”

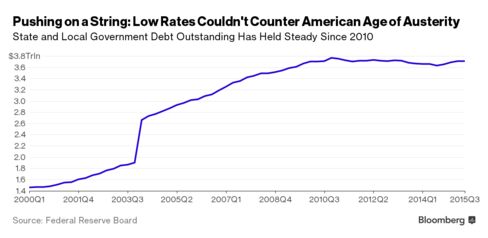

That’s the way it is across much of Louisiana. The state has added 80,000 new jobs since the Great Recession officially ended in 2009. But at the same time, jobs have been shrinking at every level of government, with local offices losing 10,600 workers, the state government 31,900 and the federal government 1,600. Louisiana is an exaggerated case, but the pattern persists when you look at the country as a whole. Since the recession hit, private employers have added five million jobs and the government has lost 323,000. The country has recovered from the recession. But public employment has not.

The public sector has long been home to the sorts of jobs that lift people into the middle class and keep them there. These are jobs that have predictable hours, stable pay and protection from arbitrary layoffs, particularly for those without college or graduate degrees. They’re also more likely to be unionized; less than 7 percent of private-sector workers are represented by a union, while more than a third of those in the public sector are. In other words, they look like the blue-collar jobs our middle class was built on during the postwar years.

The public sector’s slow decimation is one of the unheralded reasons that the middle class has shrunk as the ranks of the poor and the rich have swollen in the post-recession years. This is certainly true in Louisiana, where five of the 10 biggest employers are public institutions, or health centers that in no small part rely on public funds. In Rapides Parish, which includes Pineville, the biggest employer is the school district.

Across the country, when public-sector workers lose their jobs, the burden disproportionately falls on black workers, and particularly women — people like Theresa Jardoin and Linette Richard.

“We felt middle class,” Richard told me. “Now we feel kind of lower.”

In the middle of the last century, a series of legal and legislative decisions — fueled by and fueling the civil rights movement — increased the number of black workers in government employment. F.D.R. ended official discrimination in the federal government and in companies engaged in the war effort; Truman desegregated the armed forces; Kennedy established the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity; and Johnson signed an executive order banning discrimination by federal contractors. As a result, black workers gained more than a quarter of new federal jobs created between 1961 and 1965. And the share of government jobs held by women climbed 70 percent between 1964 and 1974, and nearly another 30 percent by the early 1980s.

Through the middle of the century, the wage gap between white and black workers narrowed as social forces and political pressure compelled private businesses to open up better jobs to black workers. “Public-sector work has been a backbone of the black middle class for many reasons,” says Mary Pattillo, a sociologist at Northwestern who studies race and class. Affirmative action helped bring marginalized groups into the public work force; there, they benefited from more public scrutiny of employment practices. “The inability to fire people in a willy-nilly fashion has likely protected African-Americans, who are perhaps likely to be fired in a willy-nilly fashion,” she says. As of 2007, black workers were 30 percent more likely than workers of other races to be employed in the public sector.

For any number of reasons, the Great Recession unraveled much of the progress made by the black middle class. Leading up to the mortgage crisis, black families tended to have a higher proportion of their wealth tied up in their homes. And regardless of their income, black families were much more likely to be rejected for conventional mortgages and pushed into high-cost subprime loans. All of this meant that when housing prices turned down, the black-white wealth gap yawned. As of 2013, white households were, on average, 13 times wealthier than black households, the biggest gap since 1989, according to Pew Research Center data.

Declining tax revenue led to tightened state budgets, which led to tens of thousands of layoffs for public-sector employees. And during the recovery, public workers became easy political targets precisely because of their labor protections. Collective-bargaining rights, pension funds and mandatory raises look like unnecessary drains on state coffers to a work force increasingly unfamiliar with such benefits. And when the layoffs came, black Americans experienced a disproportionate share of the ill effects. A graduate student of sociology at the University of Washington, Jennifer Laird, wrote a widely cited dissertation, examining the effects of public-sector layoffs on different races. She found that the government-worker unemployment rate climbed more for black men than for white men — and much more for black women than for white women, with the gap between the two groups soaring from less than a percentage point in 2008 to 5.5 percentage points in 2011. “It may be that black workers are more likely to be laid off when the layoffs are triggered by a sudden and significant reduction in funding,” she wrote. “When the number of layoff decisions increases, managers have more opportunities to discriminate.” Worse, once unemployed, black women were “the least likely to find private-sector employment and the most likely to make a full exit from the labor force.” As a result of all these economic punishments, a recession that set America back half a decade may have set black families back a whole generation, if not longer.

And because the public sector provides so many essential services, cuts to it have a cascading effect. Hospitals close, and people have to drive farther away for medical care. Teachers’ aides lose their positions, and local kids no longer have the same degree of special-education attention. Angelina Iles, the retiree I met in Pineville, cited the loss of dental, mental-health and emergency medical services as being a particularly profound problem for her community.

Other states and towns are electing to have smaller public work forces. Wisconsin, for instance, has thinned its ranks of government workers by some 5,000 since its Republican governor, Scott Walker, led a push to abrogate public workers’ organizing rights — a political choice with profound economic and racial ramifications. “They try to say that collective bargaining is a drain on the economy, when it provides the ability and opportunity for folks to have a seat at the table,” Lee Saunders, the president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, told me. And the economic evidence does show that a higher concentration of unionized workers increases intergenerational mobility and raises wages for all workers, public and private.

With time, government jobs should come back; that pathway to the middle class should grow again. “Government jobs are always slower to come back after a recession,” says Roderick Harrison, a former Howard University demographer. It takes time for private businesses to rehire workers. It takes time for tax revenue to rise to a level at which cities and states feel comfortable adding public workers back onto their payrolls. “That means that the portion of the black middle class that was dependent on government jobs — police, schools, emergency workers and so on — is going to take longer to recoup and regain whatever positions they had,” he says.

For Pineville, that recovery might come too late for many of its workers, especially those who were looking toward retirement. Because Linette Richard can’t find suitable work, she and her husband get by on what he makes as a car salesman. She has given up trying to find work again around Pineville. So has Theresa Jardoin, who has resigned herself to a tougher retirement than she thought she would enjoy.

“All of a sudden, there’s nothing,” she said, sitting in an easy chair in her living room, just blocks from Huey P. Long, playing with her granddaughter’s hair. “You can’t enjoy retirement in this situation.”

“You didn’t even get a pocket watch, did you?” Iles asked.

“No,” Jardoin said, with a resigned laugh. “Just aches and pains.”

THE NEW YORK TIMES

By ANNIE LOWREY

APRIL 27, 2016